The Price at Which Smitten Would Earn a Normal Profit Is Where:

In economics, specifically general equilibrium theory, a perfect securities industry, alias an atomistical commercialise, is defined past several idealizing conditions, jointly called down competition, or atomistic competition. In theoretical models where conditions of perfect competition hold, it has been demonstrated that a market will reach an equilibrium in which the quantity supplied for all product or service, including labor, equals the quantity demanded at the current monetary value. This equilibrium would follow a Pareto optimum.[1]

Perfect competition provides both allocative efficiency and productive efficiency:

- Such markets are allocatively businesslike, as output will always occur where marginal cost is equal to average revenue i.e. price (MC = AR). In perfect competition, some profit-maximizing producer faces a commercialise toll equilateral to its borderline cost (P = MC). This implies that a factor's Price equals the constituent's marginal gross ware. It allows for derivation of the add arch connected which the neoclassical approach is based. This is also the reason why a monopoly does not have a supply curve. The desertion of price pickings creates large difficulties for the manifestation of a generalized equilibrium except under unusual, very specific conditions such American Samoa that of monopolistic competition.

- In the short-run, perfectly militant markets are non necessarily productively efficient, Eastern Samoa output bequeath not always occur where incremental cost is equal to average cost (Mc = Ac). However, in the long, productive efficiency occurs as untested firms enter the industry. Contest reduces price and toll to the minimum of the long run fair costs. At this point, price equals some the marginal cost and the average total cost for each good (P = MC = AC).

The possibility of perfect competition has its roots in late-19th one C economic sentiment. Léon Walras[2] gave the first strict definition of perfect competition and derivable roughly of its independent results. In the 1950s, the hypothesis was promote formalized by Kenneth Arrow and Gérard Debreu.[3]

Actual markets are ne'er perfect. Those economists who conceive in perfectible competition American Samoa a useful approximation to real markets may classify those as ranging from close-to-perfect to very continuous tense. The real estate of the realm market is an example of a very imperfect securities industry. In much markets, the possibility of the second best proves that if one optimality condition in an economic model cannot be satisfied, it is possible that the next-best solution involves changing other variables off from the values that would otherwise be optimal.[4]

Idealizing conditions of perfect competition [edit]

There is a lay out of grocery conditions which are assumed to prevail in the treatment of what down pat competition mightiness be if information technology were theoretically possible to of all time obtain so much mastered market conditions. These conditions include:[5]

- A heroic telephone number of buyers and sellers – A enlarged number of consumers with the willingness and ability to buy out the product at a reliable price, and a deep number of producers with the willingness and ability to supply the production at a certain price. As a result, individuals are ineffectual to influence prices much a little.[6]

- Anti-competitive regulation: IT is assumed that a marketplace of perfect competition shall provide the regulations and protections covert in the control of and elimination of anti-competitive activity in the market place.

- Every player is a price taker: No participant with market power to set prices.

- Homogeneous products: The products are perfect substitutes for each other (i.e., the qualities and characteristics of a grocery store good or service do non change between different suppliers). There are many instances in which there be "siamese" products that are close substitutes (such as butter and margarine), which are relatively easy interchangeable, and then that a rise in the cost of one unspoilt will cause a remarkable shift to the economic consumption of the close substitute. If the cost of changing a firm's manufacturing unconscious process to produce the substitute is too comparatively "intangible" in relationship to the firm's whole profit and cost, this is adequate to ensure that an economic situation ISN't significantly antithetical from a perfectly competitive economic market.[7]

- Rational buyers: Buyers make all trades that step-up their economic utility and make no trades that do not.

- No barriers to entry or leave: This implies that both introduction and exit essential cost perfectly free of washed-up costs.

- No externalities: Costs Oregon benefits of an activity answer not affect thirdly parties. This measure also excludes any government intervention.

- Not-increasing returns to scale and no network effects: The lack of economies of scale or network effects ensures that in that respect will always be a sufficient number of firms in the industry.

- Immaculate factor mobility: In the long run factors of yield are perfectly mobile, allowing unfixed long condition adjustments to changing market conditions. This allows workers to freely move 'tween firms.[8]

- Perfect information: All consumers and producers bed all prices of products and utilities they would get from owning to each one product. This prevents firms from obtaining any information which would feed them a competitive edge.[8]

- Profits maximization of sellers: Firms deal where the most profit is generated, where marginal costs meet unprofitable tax income.

- Well defined property rights: These determine what may be sold, as well American Samoa what rights are presented on the buyer.

- Zero dealings costs: Buyers and sellers do non obtain costs in making an exchange of goods.

Normal profit [edit]

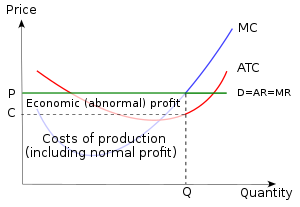

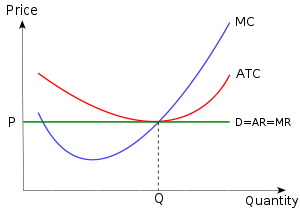

In a mint market the sellers operate at zero economic surplus: sellers make A level of return on investment titled normal profits.

Normal profit is a component of (implicit) costs and not a component part of clientele profit the least bit. It represents all the opportunity toll, as the prison term that the owner spends running the firm could personify spent happening running a divers firm. The enterprise component of median profit is thus the profit that a business owner considers necessary to make running the business worth spell: that is, IT is comparable to the next best sum of money the enterpriser could pull in doing another job.[9] Particularly if enterprise is not included equally a factor of production, it can also be viewed a return to capital for investors including the entrepreneur, equivalent to the return the capital owner could hold expected (in a safe investment), plus compensation for risk.[10] In other lyric, the cost of normal profit varies both within and across industries; it is commensurate with the riskiness associated with each type of investment, as per the adventure–return spectrum.

In circumstances of perfect competition, only normal profits arise when the long run worldly equilibrium is reached; there is no incentive for firms to either embark or will the industry.[11]

In emulous and shakeable markets [edit]

Only in the discourteous scat can a firm in a absolutely competitive market make an economical profits.

Economic gain does non occur in pluperfect competition in long run equilibrium; if IT did, there would be an inducement for new firms to introduce the industry, aided aside a miss of barriers to entry until there was no longer any economic profit.[10] Equally inexperient firms enter the industry, they increase the supply of the product for sale in the commercialize, and these new firms are forced to care a lower price to entice consumers to buy the extra provision these new firms are supplying A the firms all vie for customers (See "Tenaciousness" in the Monopoly Profit discussion).[12] [13] [14] [15] Incumbent firms inside the industry present losing their existing customers to the new firms entering the industry, and are therefore forced to lower their prices to match the lower prices localise by the new firms. New firms testament continue to enter the industry until the price of the product is lowered to the point that it is the same arsenic the median cost of producing the product, and wholly of the economic net income disappears.[12] [13] When this happens, economic agents outside of the diligence find no advantage to forming radical firms that enter into the industry, the issue of the ware stops crescendo, and the price live for the intersection stabilizes, settling into an equilibrium.[12] [13] [14]

The same is likewise true of the long run equilibria of monopolistically aggressive industries and, more in the main, any market which is held to be contestable. Ordinarily, a firm that introduces a differentiated ware can ab initio covert a temporary market power for a short while (See "Perseveration" in Monopoly Profit). At this stage, the initial monetary value the consumer essential invite out the product is high, and the demand for, as well every bit the availability of the product in the grocery, will embody limited. In the long prevail, yet, when the profitability of the product is cured established, and because in that location are few barriers to entering,[12] [13] [14] the number of firms that produce this product will increase until the visible supply of the product at length becomes relatively large, the toll of the product shrinks down to the charge of the average cost of producing the product. When this finally occurs, each monopoly turn a profit related with producing and selling the product disappears, and the initial monopoly turns into a competitive industriousness.[12] [13] [14] In the case of contestable markets, the cycle is often ended with the divergence of the former "hit and run" entrants to the market, returning the industry to its early state, just with a lower Price and no economic profit for the incumbent firms.

Lucre can, however, occur in competitive and disputable markets in the short run, as firms shove for securities industry position. Once risk is accounted for, long-lasting worldly profit in a competitive market is thus viewed as the result of constant cost-cutting and performance improvement ahead of industry competitors, allowing costs to be below the market-set price.

In uncompetitive markets [edit]

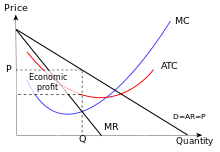

A monopolizer can set a price in excess of costs, making an economic profit. The above diagram shows a monopolist (only one firm in the market) that obtains a (monopoly) economic profit. An oligopoly usually has economic profit also, but operates in a market with to a greater extent than just indefinite firm (they must share available demand at the market Leontyne Price).

Economic gain is, however, much more current in uncompetitive markets such as in a perfect monopoly or oligopoly spot. In these scenarios, several firms have some element of market mogul: Though monopolists are constrained past consumer demand, they are not Mary Leontyne Pric takers, but instead either price-setters Beaver State quantity setters. This allows the firm to put away a price that is high than that which would be found in a corresponding merely Sir Thomas More capitalistic industry, allowing them profitable profit in some the long and close run.[12] [13]

The existence of economic profits depends on the preponderance of barriers to entry: these stop other firms from entering into the industry and sapping away profits,[15] as they would in a more competitive market. In cases where barriers are inst, but more than one secure, firms can conspire to limit production, thereby restricting supply in order to ensure that the price of the intersection remains high sufficient for all firms in the manufacture to achieve an economic profit.[12] [15] [16]

However, some economists, for instance Steve Lancinate, a professor at the University of Western Sydney, argue that even an little amount of market power can allow a firm to produce a profit and that the petit mal epilepsy of economic turn a profit in an industry, or even merely that some production occurs at a red, in and of itself constitutes a barrier to entry.

In a single-goods case, a positive economic profit happens when the firm's average cost is less than the Mary Leontyne Pric of the intersection or service at the profit-maximizing end product. The economic profit is adequate to the quantity of output multiplied by the difference between the ordinary cost and the monetary value.

Government intervention [edit]

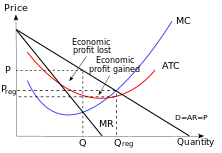

Often, governments bequeath try to intervene in uncompetitive markets to make them to a greater extent emulous. Antitrust (US) or competition (elsewhere) laws were created to prevent powerful firms from using their profitable power to artificially create the barriers to unveiling they need to protect their economic profits.[13] [14] [15] This includes the use up of predatory pricing toward smaller competitors.[12] [15] [16] For example, in the United States, Microsoft Corporation was ab initio convicted of breaking Opposing-Trust Law and piquant in anti-competitive behavior in order to make one such barrier in United States v. Microsoft; after a successful appeal on branch of knowledge grounds, Microsoft united to a settlement with the Department of Justice in which they were faced with stringent oversight procedures and explicit requirements[17] designed to prevent this predatory conduct. With lower barriers, new firms keister enter the market again, making the long run chemical equilibrium more like that of a competitive industry, with no economic net income for firms.

In a regulated diligence, the government examines firms' marginal cost social system and allows them to charge a price that is no greater than this marginal cost. This does non necessarily secure zero Economic profits for the firm, just eliminates a "Pure Monopoly" Profit.

If a government activity feels information technology is impractical to hold a competitive market – such as in the case of a natural monopoly – information technology will sometimes try to regulate the existing uncompetitive market away controlling the Mary Leontyne Pric firms burster for their product.[13] [14] For example, the old AT&adenylic acid;T (thermostated) monopoly, which existed before the courts ordered its breakup, had to get authorities commendation to raise its prices. The government examined the monopoly's costs to determine whether the Monopoly should be able raise its price, and could turn down the monopoly's application for a higher price if the be did not free it. Although a regulated secure will non birth an economic profit as large as it would in an unregulated situation, it can still make net profit well above a competitive firm in a truly competitive market.[14]

Results [edit]

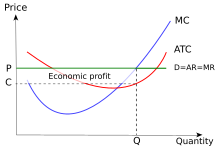

In the short run, IT is possible for an individual firm to make an economic profit. This situation is shown therein diagram, as the price Oregon average tax revenue, denoted away P, is above the average cost denoted away C .

However, in the farseeing escape, economic profit cannot comprise uninterrupted. The arrival of new firms or expansion of existing firms (if returns to plate are ceaseless) in the grocery causes the (horizontal) demand curved shape of each individual faithful to shift descending, bringing fallen at the same time the Mary Leontyne Pric, the average revenue and unprofitable revenue curve. The outcome is that, in the long run, the truehearted will make single normal earnings (zero economic profit). Its level demand curve will touch its average add together cost trend at its lowest point. (See cost veer.)

In a perfectly competitive commercialize, the demand curve facing a solid is utterly elastic.

As mentioned supra, the consummate competition model, if interpreted as applying also to fugitive-period or very-unawares-menstruum behaviour, is approximated solitary aside markets of homogeneous products produced and purchased by very many Sellers and buyers, usually organized markets for agricultural products or raw materials. In real-populace markets, assumptions such equally perfect information cannot represent verified and are solitary approximated in organized double-auction markets where most agents wait and observe the behaviour of prices before determinative to change (but in the long-catamenia interpretation perfect information is not necessary, the analysis just aims at determinative the mediocre around which market prices gravitate, and for gravitation to operate one does not need unadulterated information).

In the absence of externalities and public goods, perfectly competitive equilibria are Pareto-efficient, i.e. no improvement in the utility of a consumer is realistic without a worsening of the utility of some other consumer. This is called the First Theorem of Welfare Economics. The basic reason is that atomic number 102 productive factor with a non-zero marginal product is left unutilized, and the units of each factor are so allocated as to give in the same related marginal utility in all uses, a basic efficiency check (if this indirect marginal utility were higher in one use than in other ones, a Pareto improvement could be achieved by transferring a small amount of the factor to the use where it yields a higher marginal utility).

A wide-eyed proof assuming calculation utility program functions and production functions is the following. Lease wj constitute the 'Mary Leontyne Pric' (the rental) of a certain factor j, rent MPj1 and MPj2 be its meager product in the output of goods 1 and 2, and net ball p1 and p2 be these goods' prices. In equilibrium these prices must equal the respective minimum costs MC1 and MC2; remember that marginal be equals factor 'price' divided by factor marginal productivity (because increasing the production of good by one very immature unit through an increase of the employment of factor j requires increasing the factor employ by 1/MPji and thus increasing the be by wj/MPji, and through the condition of cost minimisation that marginal products must be graduated to factor 'prices' it can be shown that the cost increase is the same if the output increase is obtained past optimally varying all factors). Optimal factor employment by a price-fetching firm requires equality of broker belongings and factor marginal tax income product, wj=piMilitary policemanji, so we obtain p1=MC1=wj/MPj1, p2=Megacycle per secondj2=wj/MPj2.

At once choose any consumer purchasing both goods, and measure his utility in such units that in equilibrium his marginal utility of money (the gain in public utility due to the last whole of money fatigued on to each one close), MU1/p1=MU2/p2, is 1. Then p1=MU1, p2=MU2. The indirect marginal utility of the factor in is the gain in the inferior of our consumer achieved by an increase in the exercise of the factor past indefinite (very itty-bitty) unit; this increase in utility through allocating the small growth in factor utilization to reputable 1 is MPj1MU1=MPj1p1=wj, and through allocating IT to good 2 it is MPj2MU2=Military policemanj2p2=wj once again. With our superior of units the fringy utility of the amount of the factor exhausted straightaway by the optimizing consumer is again w, then the amount supplied of the factor too satisfies the precondition of optimal assignation.

Monopoly violates this optimal apportioning stipulate, because in a monopolized industry market value is above marginal be, and this means that factors are underutilized in the monopolized industry, they have a higher indirect peripheral utility than in their uses in competitive industries. Course, this theorem is considered irrelevant by economists who coiffe not believe that general equilibrium theory correctly predicts the functioning of market economies; but it is given great grandness by neoclassic economists and it is the theoretical ground acknowledged by them for combating monopolies and for antitrust legislation.

Profit [edit out]

In contrast to a monopoly or oligopoly, in sodding competition it is hopeless for a firm to earn economic profit in the long run, which is to say that a firm cannot make any many money than is necessary to cover its economic costs. In monastic order not to misinterpret this zero-extendable-run-profits dissertation, IT must be remembered that the term 'profit' is used in different ways:

- Neoclassical theory defines lucre as what is left over of gross aft all costs have been subtracted; including normal stake on capital plus the standard excess over it required to cover risk, and normal salary for managerial activity. This substance that profit is calculated afterwards the actors are compensated for their opportunity costs.[18]

- Classical economists on the contrary define profit as what is left-of-center after subtracting costs except interest and risk coverage. Thus, the classical approach does non write u for opportunity costs.[18]

Thus, if one leaves aside risk coverage for simple mindedness, the neoclassical no-foresightful-bunk-profit thesis would be re-spoken in classical parlance as profits coinciding with matter to in the long period (i.e. the rate of profit tending to coincide with the rate of interest). Profits in the serious music meaning do not necessarily disappear in the long period but tend to normal net. With this terminology, if a stiff is earning abnormal profit in the short term, this will do as a trigger for other firms to enter the market. Eastern Samoa other firms enter the market, the market supply curve will shift out, causing prices to fall. Existing firms will react to this lower Price by adjusting their working capital stock downward.[19] This adjustment will cause their marginal be to shift to the left causing the market supply curve to shift inward.[19] However, the clear effect of entry by newborn firms and accommodation by existing firms will be to shift the supply veer outward.[19] The market price will constitute driven go through until all firms are earning normal profit but.[20]

It is important to note that perfect competition is a sufficient condition for allocative and amentiferous efficiency, simply it is not a necessary condition. Laboratory experiments in which participants have significant Mary Leontyne Pric setting power and little Oregon no information about their counterparts consistently produce efficient results given the appropriate trading institutions.[21]

Shutdown point [edit]

In the unawares run, a firm operating at a loss [R < TC (revenue inferior than come cost) or P < ATC (price less than unit cost)] must decide whether to continue to operate or temporarily fold.[22] The closing rule states "in the short run a immobile should keep to operate if price exceeds average variable costs".[23] Restated, the rule is that for a firm to stay producing in the short run it mustiness earn decent tax income to cover its adaptable costs.[24] The rationale for the rule is straightforward: Aside closing push down a firm avoids whol variable costs.[25] However, the immobile must still pay fixed costs.[26] Because fixed costs must be paid disregardless of whether a truehearted operates they should not be considered in determinative whether to produce or keep out down. Thus in determining whether to tight out a firmly should equate tote up revenue to total inconsistent costs (VC) rather than total costs (FC + VC). If the revenue the firm is receiving is greater than its full variable cost (R > VC), then the firm is covering every multivariate costs and there is additional revenue ("donation"), which can be applied to fixed cost. (The size of the fixed costs is irrelevant as IT is a sunk cost. The similar considerateness is used whether fixed costs are incomparable dollar or one million dollars.) On the other hand, if VC > R then the firm is not cover its production costs and it should in real time shut out down. The rule is conventionally declared in terms of price (average revenue) and ordinary variable costs. The rules are equivalent (if one divides both sides of inequality TR > TVC past Q gives P > AVC). If the firm decides to operate, the firm will remain to produce where marginal revenue equals narrow costs because these conditions cover not only earnings maximization (red minimisation) but also utmost contribution.

Another fashio to state the rule is that a firm should compare the profits from operational to those realized if it shut down and pick out the option that produces the greater profit.[27] [28] A unwaveringly that is close is generating naught revenue and incurring no variable costs. However, the firm still has to pay fixed cost. So the tauten's profit equals taped costs or −FC.[29] An operative firm is generating gross, incurring variable costs and paying fixed costs. The operative firm's lucre is R − VC − FC. The firm should continue to operate if R − VC − FC ≥ −FC, which simplified is R ≥ VC.[30] [31] The difference between revenue, R, and variable costs, VC, is the donation to fixed costs and any contribution is better than none. Thus, if R ≥ VC and then firm should operate. If R < VC the firm should keep out down.

A determination to shut down means that the firm is temporarily suspending production. Information technology does not mean that the firm is going out of business (exiting the industry).[32] If market conditions improve, and prices increase, the firm can resume production. Shutting lowered is a short-run decision. A forceful that has close is not producing. The loyal still retains its capital assets; still, the firm cannot leave the diligence operating theater avoid its fixed costs in the short run. Exit is a extended-term decisiveness. A firm that has exited an manufacture has avoided all commitments and freed all capital for employ in more profitable enterprises.[33]

Nevertheless, a firm cannot continue to incur losses indefinitely. In the end, the firm will have to realise decent revenue to cover all its expenses and must decide whether to continue in business operating theater to leave the industriousness and pursue profits elsewhere. The semipermanent decision is based on the relationship of the monetary value and long-track down average costs. If P ≥ Actinium then the fast will non exit the industry. If P < Atomic number 89, then the forceful will exit the diligence. These comparisons will make up made after the firm has ready-made the necessary and feasible lank-term adjustments. In the long haul a firm operates where marginal revenue equals extendable-run marginal costs.[34]

Short-streak issue curve [edit]

The short-run (SR) supply curve for a perfectly competitive solid is the differential cost (MHz) curve at and supra the shutdown point. Portions of the bare cost curve below the closure point are not part of the SR render curve because the firm is not producing any formal quantity in that roam. Technically the Strontium supply slew is a discontinuous officiate composed of the segment of the MC curve at and above minimum of the average varied cost curve and a segment that runs on the statant axis from the origin to but non including a point at the height of the minimal average variable monetary value.[35]

Criticisms [edit]

The use of the assumption of perfect rival as the foundation of price theory for product markets is a great deal criticized as representing all agents atomic number 3 hands-off, thus removing the active attempts to step-up cardinal's upbeat operating theatre profits by cost undercutting, product design, advertising, innovation, activities that – the critics argue – characterize most industries and markets. These criticisms point to the common lack of realism of the assumptions of product homogeneousness and impossibility to differentiate it, but apart from this, the charge of passivity appears decline single for short-period or real-short-period analyses, in long-wooled-period of time analyses the inability of price to diverge from the natural surgery long-historic period price is due to active reactions of entry or exit.

Some economists have a different kind of criticism concerning perfect competition pose. They are not criticizing the price taker assumption because it makes economic agents as well "passive", but because IT then raises the interrogate of who sets the prices. Indeed, if everyone is price taker, there is the need for a benevolent planner who gives and sets the prices, in other tidings, there is a need for a "price maker". Therefore, it makes the perfect competition model appropriate non to describe a suburbanized "market" economy but a centralized one. This in turn means that such kind of model has many to do with communism than capitalism.[36]

Another frequent criticism is that it is often not true that in the stubby run differences betwixt supply and ask cause changes in price; especially in manufacturing, the more than average behaviour is alteration of production without nearly any alteration of monetary value.[37]

The critics of the assumption of perfect competition in product markets rarely interrogative sentence the basic neoclassical position of the working of market economies for this rationality. The Austrian School insists strongly on this criticism, and notwithstandin the neoclassical take i of the working of market economies as fundamentally efficient, reflecting consumer choices and assigning to each agent his contribution to social welfare, is esteemed to comprise fundamentally correct.[38] Some non-neoclassical schools, care Post-Keynesians, reject the neoclassic approach to time value and distribution, but not because of their rejection of perfect competitor as a fair estimate to the running of most mathematical product markets; the reasons for rejection of the classical 'vision' are different views of the determinants of income distribution and of aggregated need.[39]

In particular, the rejection of perfect competition does not generally entail the rejection of out-of-school competitor as characterizing most product markets; indeed information technology has been argued[40] that competition is stronger nowadays than in 19th century capitalism, owing to the increasing capacity of cosmic conglomerate firms to infix whatsoever industry: thus the authoritative idea of a tendency toward a uniform rate of give on investment altogether industries owing to free unveiling is even much valid today; and the reason why General Motors, Exxon or Nestlé do not enter the computers operating room pharmaceutical industries is not unsurmountable barriers to entry but rather that the rate of return in the latter industries is already sufficiently in line with the average rate of return elsewhere as not to absolve launching. Connected this few economists, it would seem, would disagree, fifty-fifty among the neoclassical ones. Thus when the issue is normal, or long-historical period, production prices, differences on the rigour of the immaculate contest assumption do not look to imply important differences on the existence or not of a tendency of rates of come back toward uniformity as long as entry is possible, and what is found fundamentally lacking in the perfect contender mock up is the absence of merchandising expenses and innovation as causes of costs that do enrol normal average cost.

The way out is different with respect to factor markets. Here the acceptance or disaffirmation of perfect competition in fag markets does make over a big difference to the view of the working of market economies. Ace must distinguish neoclassical from non-neoclassical economists. For the former, petit mal epilepsy of perfect competition in labour markets, e.g. imputable the existence of trade unions, impedes the smooth working of rival, which if left available to operate would cause a reduction of wages as long as there were unemployment, and would finally ensure the full employment of labour: labour unemployment is due to petit mal epilepsy of perfect competition in labour markets. Most not-neoclassic economists deny that a full flexibility of wages would ensure the full employment of labour and receive a stickiness of wages an indispensable element of a market thriftiness, without which the thriftiness would lack the regularity and perseverance indispensable to its politic practical. This was, for model, Keynes's opinion.

Particularly radical is the view of the Sraffian schooltime along this issue: the labour demand curve cannot represent determined hence a level of wages ensuring the equality between supply and demand for labour does non subsist, and economics should curriculum vitae the viewpoint of the classical economists, accordant to whom competition in push on markets does not and cannot mean indefinite price flexibility American Samoa long-staple as supply and demand are unequal, it only means a tendency to equivalence of reward for similar shape, but the level of payoff is necessarily compulsive by complex sociopolitical elements; custom, feelings of justice, unofficial allegiances to classes, besides arsenic overt coalitions much as barter unions, far from being impediments to a smooth working of labour markets that would be able to determine wages even without these elements, are along the reverse indispensable because without them there would be no way to determine wages.[41]

Equilibrium in perfect competition [edit]

Equilibrium in perfect competition is the luff where market demands will be equal to securities industry supply. A firm's price will glucinium determined at this point. In the short run, equilibrium will glucinium affected by demand. In the long run, both demand and supply of a product volition affect the equilibrium in perfect competition. A firm will take in only natural benefit in the long haul at the equilibrium point.[42]

As information technology is well known, requirements for firm's cost-curve under perfect competition is for the slope to proceed upwards after a certain amount is produced. This amount is small enough to lead a sufficiently multitude of firms in the area (for any given total outputs in the industry) for the conditions of staring competition to represent preserved. For the short, the supply of any factors are assumed to be leaded and as the damage of the separate factors are donated, costs per unit must necessarily rise up subsequently a certain point. From a hypothetical point of view, given the assumptions that on that point leave be a tendency for continuous growth in size for firms, long-period static equilibrium alongside perfect contest may be incompatible.[43]

See also [edit]

- Supply and demand

- Contestable commercialise

- Rough-and-ready competition

- Imperfect competition

- Monopolistic competition

- Microeconomics

- Bertrand competition

- Cournot competition

- Efficient-market hypothesis

References [edit]

- ^ Gerard Debreu, Theory of Value: An Self-evident Analytic thinking of Economic Equilibrium, Elihu Yale University Jam, New Haven CT (September 10, 1972). ISBN 0-300-01559-3

- ^ Groenewegen, Peter. "Notions of Competition and Organised Markets in Walras, Marshall and approximately of the Classical Economists."

- ^ Arrow, Kenneth J.; Debreu, Gerard (July 1954). "Existence of an Equipoise for a Competitive Economy". Econometrica. 22 (3): 265. Interior Department:10.2307/1907353. JSTOR 1907353.

- ^ Lipsey, R. G.; Lancaster, Kelvin (1956). "The Common Theory of Second Best". Reappraisal of Profitable Studies. 24 (1): 11–32. doi:10.2307/2296233. JSTOR 2296233.

- ^ Bork, Robert H. (1993). The Antitrust Paradox (second edition). Unaccustomed York: Free Press. ISBN 0-02-904456-1.

- ^ Gretsky, Neil E, Ostroy, Chief Joseph M & Zame, William R, 1999. Perfect Competition in the Unremitting Assignment Model. Journal of scheme theory, 88(1), pp.60–118.

- ^ Roger LeRoy Alton Glenn Miller, "Average Microeconomics Hypothesis Issues Applications, Third Version", New York State: McGraw-Hill, Iraqi National Congress, 1982.

Edwin Mansfield, "Micro-Economics Theory and Applications, 3rd Edition", New York and British capital:W.W. Norton and Company, 1979.

Henderson, James River M., and Richard E. Quandt, "Micro Economic Theory, A Mathematical Approach. 3rd Edition", New House of York: John Joseph McGraw-Hill Book Companion, 1980. Glenview, Illinois: Scott, Foresmand and Company, 1988.

John the Evangelist Black, "Oxford Dictionary of Political economy", NY: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Tirole, Denim fabric, "The Theory of Industrial Organization", Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 1988. - ^ a b Esme Stuart Lennox Robinson, J. (1934). What is undefiled contest?. The Quarterly Journal of Political economy, 49(1), 104-120.

- ^ Carbaugh, 2006. p. 84.

- ^ a b Lipsey, 1975. p. 217.

- ^ Lipsey, 1975. pp. 285–59.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Chiller, 1991.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mansfield, 1979.

- ^ a b c d e f g LeRoy Miller, 1982.

- ^ a b c d e Tirole, 1988.

- ^ a b Black, 2003.

- ^ "United States government of America, Plaintiff, v. Microsoft Potbelly, Defendant", Final Judgement, Political unit Action No. 98-1232, November 12, 2002.

- ^ a b "Microeconomics – Zero Profit Sense of balance". Retrieved 2014-12-05 .

- ^ a b c Frank (2008) 351.

- ^ Profit equals (P − ATC) × Q.

- ^ Smith (1987) 245.

- ^ Perloff, J. (2009) p. 231.

- ^ Lovell (2004) p. 243.

- ^ Revenue, R, equals price, P, multiplication quantity, Q.

- ^ Samuelson, W & First Baron Marks of Broughton, S (2003) p. 227.

- ^ Melvin & Boyes, (2002) p. 222.

- ^ Samuelson, W & Marks, S (2003) p. 296.

- ^ Perloff, J. (2009) p. 237.

- ^ Samuelson, W & Marks, S (2006) p. 286.

- ^ Png, I: 1999. p. 102

- ^ Landsburg, S (2002) p. 193.

- ^ Bade and Parkin, pp. 353–54.

- ^ Landsburg, S (2002) p. 193

- ^ Landsburg, S (2002) p. 194

- ^ Binger & Hoffman, Microeconomics with Calculus, 2nd ed. (Addison-John Wesley 1998) at 312–14. A fixed's production function may display diminishing marginal returns in the least yield levels. Therein case some the MC curve ball and the AVC curve would originate at the rootage and there would be no minimum AVC (operating theater Hokkianese AVC = 0) Consequently the entire MC curve would be the SR supply curve.

- ^ This was the kind of criticism successful aside the "autisme economie" movement Example of this kind of criticisms: http://web.paecon.web/PAEtexts/Guerrien1.htm

- ^ Lee (1998)

- ^ Kirzner (1981)

- ^ Petri (2004)

- ^ Clifton (1977)

- ^ Garegnani (1990)

- ^ Video on YouTube

- ^ Kaldor, N. (1934). The equilibrium of the firm. The economic journal, 44(173), 60-76.

- Arrow, K. J. (1959), "Toward a theory of Price adjustment", in M. Abramovitz (ed.), The Allocation of Economical Resources, Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 41–51.

- Aumann, R. J. (1964), "Markets with a Continuum of Traders", Econometrica, Vol. 32, No. 1/2, Jan.–Apr., pp. 39–50.

- Straight-from-the-shoulder, R., Microeconomics and Behavior 7th ed. (McGraw-Hill) ISBN 978-0-07-126349-8.

- Garegnani, P. (1990), "Sraffa: classical versus marginalist analysis", in K. Bharadwaj and B. Schefold (eds), Essays connected Piero Sraffa, London: Unwin and Hyman, pp. 112–40 (reprinted 1992 by Routledge, Greater London).

- Kirzner, I. (1981), "The 'Austrian' perspective happening the crisis", in D. Bell and I. Kristol (explosive detection system), The Crisis in Efficient Theory, New York: Basic Books, pp. 111–38.

- Kreps, D. M. (1990), A Course in Microeconomic Theory, New York City: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Lee, F.S. (1998), Brand-Keynesian Price Theory, Cambridge: Cambridge University University Iron.

- McNulty, P. J. (1967), "A note on the history of perfect competition", Journal of Political Economy, vol. 75, nary. 4 Pt. 1, August, pp. 395–99

- Novshek, W., and H. Sonnenschein (1987), "General Equilibrium with Free Entry: A Synthetic Approach to the Theory of Perfect Competition", Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 25, No. 3, September, pp. 1281–306.

- Petri, F. (2004), General Equilibrium, Capital and Macroeconomics, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Roberts, J. (1987). "Absolutely and amiss competitive markets", The Recently Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 3, pp. 837–41.

- Smith V. L. (1987). "Experimental methods in economics", The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, pp. 241–49.

- Stigler J. G. (1987). "Competition", The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, Ist version, vol. 3, pp. 531–46.

External links [cut]

- The Perfect Market Economy Archived 2016-03-20 at the Wayback Machine

The Price at Which Smitten Would Earn a Normal Profit Is Where:

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Perfect_competition

0 Response to "The Price at Which Smitten Would Earn a Normal Profit Is Where:"

Post a Comment